If you are going to be debating in one of our tournaments at the Luddy schools, it will help you to know that the Coolidge Foundation has a distinctive approach to debate. Two important things for you to know about are our debate format and our debate style.

Format

In this league, students debate in teams of two. It is most similar to team policy debate, but with shorter times. The timing and order of speeches is as described below. Please familiarize yourself with it, as it might differ from other formats that you have heard of or seen at other tournaments.

1. First Affirmative Constructive: 4 mins

2. Cross-examination: 2 mins

3. First Negative Constructive: 4 mins

4. Cross-examination: 2 mins

5. Second Affirmative Constructive: 4 mins

6. Cross-examination: 2 mins

7. Second Negative Constructive: 4 mins

8. Cross-examination: 2 mins

9. First Negative Rebuttal: 3 mins

10. First Affirmative Rebuttal: 3 mins

11. Second Negative Rebuttal: 3 mins

12. Second Affirmative Rebuttal: 3 mins

Debaters should not raise new arguments during rebuttals. Both teams will receive 5 minutes of prep time which can be used when desired between speeches.

Style

In this league, we instruct our judges to reward clear communication, logical thinking, and the use of quality evidence. Although many of our judges themselves have experience debating or judging, we also invite and encourage citizen judges (i.e., lay judges) to partake in our tournaments. You should assume that your judge is listening to see who makes the best overall case for his or her side. To that end, we recommend you prepare your argumentation with the following advice in mind:

1. Content is of utmost importance.

Content mastery is perhaps the most important factor in our debates. Debaters will be judged carefully based on the quality of their arguments and evidence. Debaters should take extreme care to ensure they understand the arguments they are making, and that their evidence comes from reliable, trusted sources. Primary sources, facts and figures from government-published databases, scholarly research, academic articles, books, and other publications are examples of high-quality evidence.

2. Speak at a conventional public pace.

Speak clearly and efficiently, and do so at a pace that a layperson can understand. When President Coolidge gave a speech on the campaign trail, a radio address, or made a plea to Congress, he did not do so at 300 words per minute. Your goal should be to communicate your thoughts, not overwhelm the judge or your opponent with the speed of your speaking.

3. Focus on quality over quantity.

Choose the major points that you want to make, and make them clearly. Take the time to define key terms, provide vivid examples, or cite evidence that back your claims. Particularly with constructive speeches, it is better to lay out three to five good points than to make ten or more weak or unsupported points. President Coolidge, a great economizer of words, would want to know what your main ideas are; he would not be moved by superfluous ones.

4. Stay on topic.

Debate the resolution. Do not radically redefine the resolution, or isolate some small component of the resolution and attempt to win the debate by ignoring the essence of the issue. The judges have been informed that staying on topic is highly important and that debaters who fail to debate the intended resolution will lose the debate round. Don’t make the whole round an argument about definitions and burdens.

5. Don’t fixate on procedural technicalities.

We familiarize our judges with basic debating conventions — however, since we make use of citizen judges, it would not be wise to stake your entire case on calling out a minor procedural foul or transgression of an opponent. President Coolidge would expect you to win primarily on the merits of your own arguments, not by your opponent’s mishap.

6. Be civil.

Above all, exercise civility in your arguments and toward your opponent and judge. Just as President Coolidge was more concerned with character and principle than with political expedience or his personal historical legacy, resist any temptation to resort to incivility during your debate. Be incisive, resilient, or even adamant, but don’t be anything less than civil.

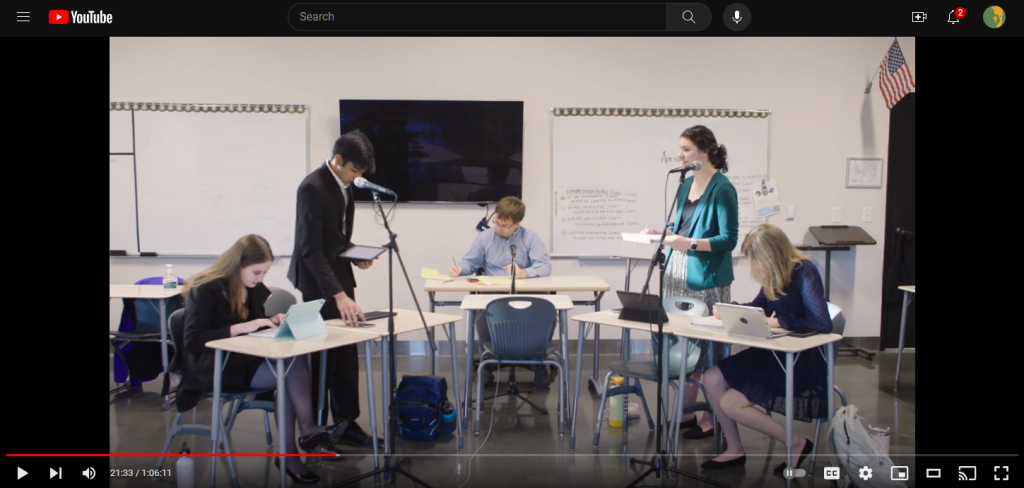

Example Round

The students of Thales Academy have put together a video of a mock debate to serve as an instructional example for students and coaches who are new to Coolidge 2v2 format. View it here.

How to Use the Debate Brief

Relevant arguments are important in this debate league. With that in mind, the Coolidge Foundation creates a debate brief that outlines important and evidence-based arguments for both sides of the resolution. The brief also includes a section with background on the topic and definitions of key terms. Arguments from outside the brief are both permitted and encouraged, but debaters should carefully evaluate the logic of the arguments that they use.

Using Evidence

Quality evidence is also important in this debate league. Evidence from outside the brief is permitted and encouraged, but debaters should carefully evaluate the evidence that they use, and only use evidence that they genuinely believe is good and reliable. You may ask your opponent about the evidence that he or she is using, but unlike standard high school policy debate, this league does not expect debaters to prepare evidence cards and “call” for them during the debate. Also, debaters are not allowed to bring in visual aids such as posters, handouts, or printed graphs. If there is a graph or diagram that you’d like to incorporate into your argument, practice describing it in words.

Should I Quote or Mention President Coolidge?

Yes! Although you are not required to quote President Coolidge in a Coolidge Debate, we of course do look favorably upon incorporating the President’s words and deeds into your arguments. (To be clear, students will not be marked down for failing to reference Coolidge or quote him, but students who do reference or quote him likely will be marked up for it.) This is in keeping with the generally accepted advice that in debate one should acknowledge the context in which one is speaking and the audience to whom one is speaking. Since we are the Coolidge Foundation, it is a safe assumption that the citizen judges you will encounter have a generally positive impression of President Coolidge and thus would enjoy hearing how you recognize that in your speaking.

Policy on Electronic Devices

Electronic devices such as laptops, tablets, and mobile phones may be used as long as they are not connected to the Internet during the round. To ensure fairness, please put your device in airplane mode (i.e., turn off your devices WiFi and cellular capabilities) during the round. Keep in mind that, just as with written notes, the less you handle and read from your screens, the better. Judges will look at heavy reliance upon electronic devices negatively, just as they look at heavy reliance upon written notes negatively.

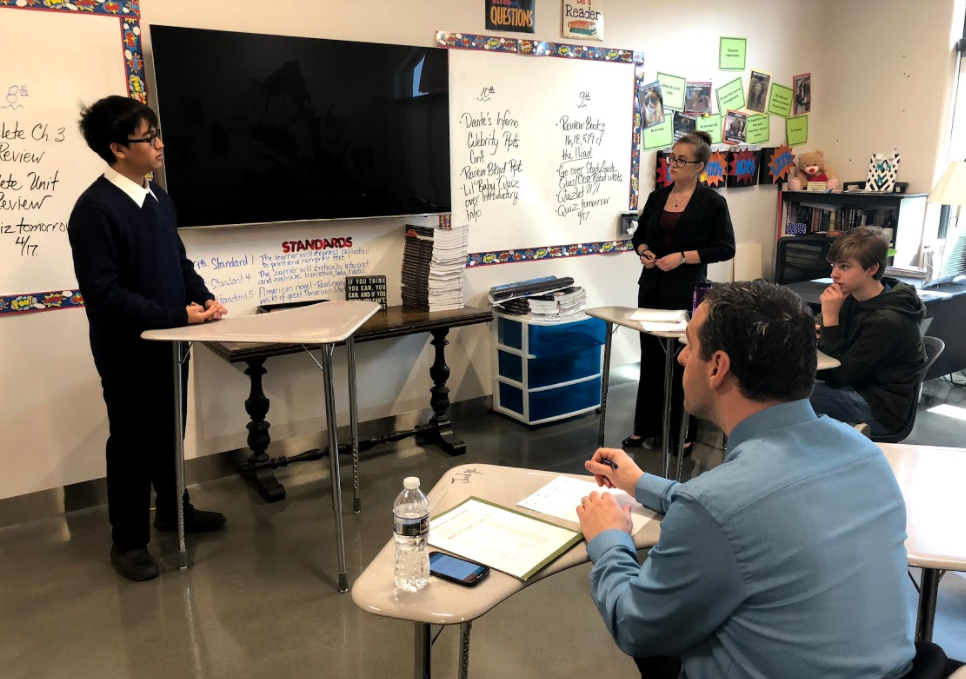

Students compete in a tournament at Thales Academy Apex in April 2018