Coolidge in Virginia, Thanksgiving 1928

By Carthon W. Davis, III

Carthon Davis, III is a native of Staunton, Virginia. He is a history major, with a concentration in archaeology, at the University of Mary Washington, Fredericksburg, Virginia. He would like to thank Dr. Howard F. McMains and Dr. Robert H. Ferrell for generously reading and commenting on an earlier version of this article.

When President and Mrs. Coolidge traveled to Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains for the 1928 Thanksgiving holiday, they were doing what many Americans were beginning to do, they were taking a vacation. From Washington to Lincoln presidents traveled little and certainly not for pleasure. Gilded Age and Progressive Era presidents occasionally returned to Eastern or Midwestern places they knew. By the 1920s, railroads and automobiles made it possible even for a president to take a “vacation.” The idea for a permanent presidential retreat had yet occurred. Coolidge traveled several times to the place he knew, Plymouth Notch, and to such places as Swampscott, Massachusetts, and White Pine Camp, in the Adirondacks of New York. He most famously vacationed near Rapid City, South Dakota, where in 1927 he chose not to run. In the summer of 1928, he vacationed near Superior, Wisconsin, and for Thanksgiving traveled to a luxurious mountaintop hotel in Virginia, where the first couple spent several days.

In early 1928, the White House began to search for a site where Coolidge could spend his last summer vacation as president, without yet thinking of Thanksgiving later in the year. Invitations began arriving in February and March from such places as Southampton on Long Island and a farm in Connecticut. Before long the White House received letters recommending each place.

The most likely seemed to be Swannanoa Country Club near Afton, Virginia, which sent an invitation on March 24.1 Five days later, C. Bascom Slemp, an ex-Virginia congressman and Coolidge’s secretary early in the first term, wrote a personal letter supporting the idea of Swannanoa. He wrote that the club was “on the top of the Blue Ridge and on the edge of the great National Park you have established.” He coyly added that the park should have been named “Coolidge National Park.” Slemp felt that Virginians would be honored to host the president for the summer and that the vacation would restore relations between Virginia and Massachusetts as they had been in the Republic’s early days. Next day, Virginia’s Democratic governor, Harry F. Byrd, reiterated the invitation, by going to the White House with Slemp and Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin, responsible for the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg.2 Coolidge was favorable to the idea of Swannanoa and spoke of sending a representative to inspect the place. During the meeting, the president expressed an interest in fishing, and within a couple of days Byrd received a letter from Hierome L. Opie, president of the Leader Publishing Company, giving a detailed survey of fishing around the club.3

|

| Coolidge Trapshooting at Swannanoa December 1, 1928 (personal collection of the author) |

Virginia’s invitation seemed to move forward. On May 2, Colonel Edmund W. Starling, the President’s bodyguard, met Governor Byrd and others in Richmond, and drove to Swannanoa. After viewing the possible “summer White House,” Starling reported that he was pleased. He noted that in nearby Waynesboro was the location of Fairfax Hall, a girl’s school where executive officials and newspaper reporters could be housed in unoccupied buildings. The Staunton News Leader reported May 4 that Swannanoa had been the only summer place that Starling inspected but others would see other sites at a later date. Coolidge announced that he still had not chosen a summer place but did not want to be as far from Washington as in previous years.4

Virginians were dismayed when the president on May 31 decided to spend his summer in a cabin on the Brule River in Wisconsin. Although he had said he wanted to be near Washington for personal reasons, he chose a place distant from the capital and in an area unaffected by political considerations.5 The secretary-manager of the Richmond Grocery Company, Sam Heeler, wrote, “To say the least I was much disappointed when I read the news item that you had decided to spend your summer vacation in Wisconsin.” Heeler recalled testily that he sought to provide the president with a Smithfield ham and the president had agreed to give Swannanoa special consideration. He had made plans to meet the presidential party at Swannanoa and present the ham baked and ready for the table. “We Virginians are much disappointed that you will not be with us this summer,” he concluded. Thereafter, on his vacation in Wisconsin, Coolidge relaxed and fished, just as he wanted, and was introduced to a new sport, trapshooting. On July 26, he received two shotguns, traps, and clay pigeons, and his staff reported that Coolidge was enthusiastic.6

Looking towards Thanksgiving, the Swannanoa Club sent another invitation and Gov. Byrd again visited the president, this time with success. On October 17, the White House announced that the Coolidges would spend their November holiday in Virginia. The president would leave the capital on Wednesday, November 28, and return Sunday, December 2. Some days later Colonel Starling returned to Richmond and met Major A. Willis Robertson, chair of the state commission of game and inland fisheries, to discuss plans for the presidential party to go hunting. The hunt was planned for two days, which allowed the president to hunt on one or both days. Out of concern that crowds would overwhelm the event, location was not disclosed. Moving pictures were to be taken for the public to view at theaters throughout the country. It was planned that only the president would carry a gun in the field. The Commonwealth of Virginia issued a non-resident hunting license to the president, costing him $15.50.7

Further plans followed. On October 18, Coolidge received an invitation from President Edwin Alderman of the University of Virginia to attend a buffet luncheon and football game on Thanksgiving Day. The two men had previously corresponded on an array of topics, including Alderman’s idea of adding an Institute of Public Affairs to the university.8 The plan was for Byrd to meet the presidential party at Swannanoa upon arrival and invite them to the game, a classic Thanksgiving match between the rival universities of Virginia and North Carolina. On November 19, the First Baptist Church in Charlottesville invited Coolidge to attend the annual Thanksgiving Day union service, which included all the local churches. Slemp suggested that the party go to the service and then afterwards to the luncheon and game.9

Meanwhile the University of Virginia anticipated the Thanksgiving game would attract the largest crowd to see a football match in the state, due to Coolidge’s attendance. Gov. Byrd and Democratic Gov. McLean of North Carolina were invited and accepted, thus providing a distinguished combination of Democrats and Republicans at a southern event. The university built additional bleachers to accommodate 15,000 spectators. Altogether about 20,000 tickets were sold, and some fans had to stand. A box was constructed for the presidential party and another for newspaper reporters and photographers. The Monticello Guard would escort the president while in Charlottesville. They would wear colonial uniforms of cocked hats, knee breeches, leggings. The municipal band of Charlottesville, known for appearances at annual reunions of Confederate veterans, would provide music.10

Further plans were being made. Coolidge released his Thanksgiving proclamation on Sunday, November 25, so the duty would not interfere with his vacation. The counties of Albemarle, Augusta, and Nelson, where activities had been planned, made preparations. For the president’s security, twelve secret service agents would accompany him but stay at a hotel in Waynesboro, four miles from Swannanoa. There would be fifteen reporters and photographers, and they would stay at the Stonewall Jackson Hotel in Staunton, fifteen miles away. The mayor of Charlottesville asked that the city be decorated and streets be lined with American flags.11

President and Mrs. Coolidge had invited close friends, Mr. and Mrs. Frank W. Stearns of Boston. Mrs. Stearns became so ill that she and her husband remained at the White House, the illness being reported as minor. Coolidge had the White House physician, Colonel James F. Coupal, remain in Washington with Mrs. Stearns. Replacing Coupal for the trip was Lieutenant-Commander W. J. C. Agnew, a Navy medical officer. Also accompanying the president were Army Colonel Osmun Latrobe and Navy Captain Wilson Brown. In addition, nine White House servants went along to ensure presidential comfort.12

The morning of November 28, the presidential party left Washington for the five-day vacation atop the Blue Ridge Mountains, and by 1:00 p.m., the president’s special train had reached Main Street Station in Charlottesville. Five hundred people were able to see the president and Mrs. Coolidge while the train switched engines. The first couple sat in a private car, the Patrick Henry, one of the most modern on the Chesapeake and Ohio. The Charlottesville Daily Progress reported that the president just sat with a pencil and paper in hand, paying little attention to the crowd, while Mrs. Coolidge petted her favorite collie, Prudence Prim. The couple remained seated until the train began pulling out, when they both stood. The president doffed his hat and Mrs. Coolidge waved to the cheering crowd.13

An hour later, the train arrived at Waynesboro, where the party switched to automobiles for the remainder of the trip. Waynesboro received Coolidge in presidential fashion. Cadets from the Fishburne Military Academy were arrayed to welcome the president, and a band played “Hail to the Chief,” amidst a twenty-one gun salute.

From Waynesboro, state police escorted the cavalcade up the mountain to the club, built in 1912. It was a palace of white Georgia marble, perched 2,400 feet above the Rockfish and Shenandoah valleys, overlooking places where many skirmishes and battles occurred during the Civil War. The Washington Post commented that “over these mountains many men marched to their rendezvous with death.” That this history-soaked area became the Republican president’s seat of government seemed a symbolic gesture to Coolidge, who had expressed a desire to remove all sectionalism in the country by the end of his term.14

When the party reached Swannanoa, E. M. Crutchfield and a group of club officials greeted them. Photographers took pictures as the group went up the steps to the club’s entrance. President Coolidge suggested taken photos of him with two local men and did so with a broad smile, a moment so surprising that a photographer shouted, “He’s smiling, keep it going.”15 Inside, President and Mrs. Coolidge received a ten-pound “old fashion” fruitcake. Gov. Byrd was supposed to be in attendance but was delayed. He presented his greetings the next day, along with the president’s hunting license and the invitation to the next day’s football game. Mrs. Coolidge toured the estate and its scenic gardens with Tiny Tim, the reddish brown White House chow.

For the first evening’s entertainment, there was a program of talking motion pictures. “Talkies” were the wonder of the day, the first full-length movie with sound having appeared in October 1927. The films included speeches by King George V of Great Britain and King Alphonso of Spain. Coolidge had the unusual experience of seeing and hearing himself read his Thanksgiving proclamation. As the films started, all five of the White House dogs started barking at the screen. The president arose and helped drive out the dogs. The films started again.16

Earlier the president’s son, John, had announced his engagement to Florence Trumbull, daughter of Governor and Mrs. John H. Trumbull of Connecticut; November 28 was the Trumbulls’ twenty-fifth anniversary.17

The president began Thanksgiving morning early, and it would be a long day. He practiced his new interest in trapshooting. Club officials had installed new traps, and from forty yards, he shot seventeen of twenty-five clay pigeons.18 At 9:00 a.m., the party left for Charlottesville. Outside the First Baptist Church, a crowd had gathered. When Coolidge arrived, he was greeted by two men, who escorted him and Mrs. Coolidge to their pew. A thousand people packed the church, and they stood and applauded when the party entered. The service began with a prayer for recovery of the ailing King George, then the pastor, the Rev. J. W. Moore, delivered the sermon. His story was Esther, influential and had opportunity to save her people. He related the story to the history of the United States by saying it was the nation’s obligation to bring peace to a “war-cursed and shell-shocked world.” The president sat quietly and seemed to listen to the sermon. At the end, the president and Mrs. Coolidge were escorted out as moving picture cameras recorded them. The president spoke with Governors Byrd and McLean, who also attended. They posed for more pictures on the church steps.19

From the church, the party traveled to President Alderman’s house for luncheon, where guests were Grace Coolidge and Edith Wilson, widow of President Woodrow Wilson. Attending were both governors and several citizens from Virginia and North Carolina. Mrs. Wilson took the opportunity to talk with four of the secret service men who had served in the White House during the Wilson administration. They sat in the Aldermans’ parlor and reminisced.20 An entry in the diary of Lewis Catlett Williams, a member of the Virginia’s board of visitors from 1922 to 1946, speaks briefly of the luncheon: “The Pres. said nothing, but Mrs. C. was very gorgeous and pleasant. Mrs. Woodrow Wilson was charming as usual.”21

After the luncheon, the presidential party went to Lambeth Field through flag-bedecked streets, and everyone cheered. They arrived at 2:25, five minutes before the game, and Coolidge received a standing ovation. He had planned to stay for only ten minutes but remained for the first quarter. He did not see North Carolina’s narrow victory. It was the first time a sitting president had attended a football game in Virginia. A student had written to his mother that the president’s attending “the big game” was “quite a celebration.”22

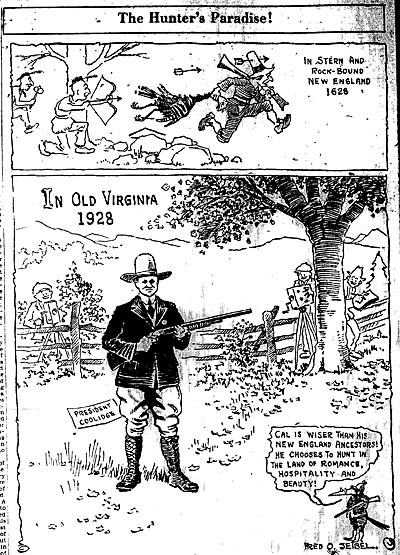

The president thought the feeling of sectionalism was gone because of the warm reception on the streets and at the game. Slemp thought the reception indicated the beginning of a new political alignment. Democrats and Republicans felt that Slemp was responsible for bringing Virginia and North Carolina into the Republican column in the last presidential election and even predicted that he would have a place in Herbert Hoover’s cabinet when Hoover became president. Coolidge avoided discussing the election except for a couple of references, both to Governor Byrd. At the luncheon, he said he was pleased with the cartoon in that morning’s Richmond Times-Dispatch. At the game he said, “Governor, between the two Republican states of North Carolina and Virginia, it looks like I’ll have to be very careful how I root.” Otherwise, the two men sat beside each other and Coolidge remained “Silent Cal.”23

From Charlottesville, the party returned to Swannanoa, but an incident occurred on the road leading to the club. A car blocked the road, and agents ran forward and questioned the driver. He was cleared of suspicion when he said he had sneaked onto the grounds so he and his girlfriend could see the president. He had managed to pass the state police guards at the club’s gate by telling them he was a former secret service agent and wanted to see his old colleagues. The man was forced to drive off the property before the party continued.

The Coolidges spent a very quiet Thanksgiving evening. The only commotion occurred when Byrd and McLean arrived to pay their respects. After their visit, the Coolidges had Thanksgiving dinner alone since Mr. and Mrs. Frank Stearns remained at the White House. The meal featured a turkey, which “tipped the scales at 30 pounds, a bronze, deep-cheated fowl fit to grace the table of any ruler,” according to the Staunton News Leader’s breathless report. The menu was a traditional soup-to-nuts affair, including clear soup, celery and olives, chestnut dressing and cranberries, puree of chestnuts, onions, squash, Virginia yams, avocado salad, mince pie, nuts. After the meal, the Coolidges spoke by telephone with their son and his fiancée, Miss Trumbull. They relaxed and listened to the radio and “Fox Movietone” concerts. It was planned that the remainder of the time at Swannanoa would be for rest, with trapshooting for the president and hiking for the first lady.24

|

| Richmond Times Dispatch November 30, 1928 |

The next day was full of relaxation and enjoyment with being away from the capital. The president and Mrs. Coolidge awoke early and went for a short walk around the estate, though there was fog and drizzling rain.25 Back at the club, Coolidge waited for a change in the weather so he could venture outdoors again. While he waited, he met with Henry Tucker, the local congressman. Tucker presented the president with more food, this time Virginia sausage as an additional breakfast item. Once Tucker left and breakfast was over, Coolidge retired to a sheltered porch in front of the palace where he paced and kept an eye on the dark clouds. The rain continued all day. He read and listened to the radio. Mrs. Coolidge stayed indoors and, it was said, knitted wool socks for her son. The president did receive an invitation to go quail hunting on a local estate owned by A. R. Moorehead, but the weather caused postponement to the next day. The Coolidges did brave the weather and ventured outside. The president went to the traps to practice shooting, hitting two more clay pigeons than the day before. Mrs. Coolidge walked her dogs. She had some unexpected excitement when a rabbit began leading the dogs on a merry chase.

The Coolidges received gifts on this day, mostly food. They received six boxes of apples from a local orchard. They received another Virginia ham, prepared by May Vennie, considered the area’s best cook of traditional fare and who had once prepared a meal for Marshal Ferdinand Foch and General John J. Pershing when they had visited state. They also received good news from Washington, for it was said that Mrs. Stearns’ health was improving.26

Saturday, December 1, the weather cleared at mid-day and Coolidge went quail hunting on an estate seven miles away, in the Shenandoah Valley and near the town of Stuarts Draft. Moorehead, the owner, assured the president the land was full of quail and practically assured that the president would bag a few. Coolidge wore hunting attire composed of gifts from prior vacations: a green mackinaw given him in Wisconsin, and a broad sombrero from South Dakota, the costume completed by a pair of hunting breeches and high-laced boots. Coolidge could not bad a single bird, even though the land had not been hunted for five years. Five times a bird flew, and each time the president missed. At the end of the day, those with him praised his handling of the gun but allowed the gun might be inadequate, perhaps having too long a barrel for the shot sufficiently to spread, they claimed.27

On the way back, Coolidge saw a girl walking up a mountain with what appeared to be a heavy load. He had the chauffeur stop and a secret service agent ask if she wanted a ride. The girl was awestruck and ran down a side road. Later, Coolidge decided again to shoot clay pigeons. Wearing the same costume as for the quail hunt, he missed the first two targets before taking off the mackinaw and then succeeded in taking down the next two. No score was kept but photographers and sound motion-picture cameras were on hand to capture the president “blazing away at the flying discs.”28

That night the president and first lady invited thirty local residents who had helped with the vacation. Once again, talkies were shown.29 Crutchfield gave a speech that returned to the theme of Coolidge’s success in helping remove sectionalism.

- The young men of today and even older ones will turn to history and refresh their memories of the traditions of old Virginia and the stability of her early statesmen in the formative periods of the nation. . . . Of late years, century-old sympathies have reasserted themselves and Virginia and Massachusetts have stood closer together. And the President of the United States by coming here has aided that movement. . . .30

Newspaper stories were positive. According to the New York Herald Tribute,

- Sixty years ago Virginia was in the midst of that period of reconstruction…. “Yankee” and “Republican”… [were] pet epithets of opprobrium. Yet here is a Republican President…received by all classes of the population with every mark of esteem and affection…a demonstration that the wounds of a young country heal quickly leaving no scars.31

The last day of vacation proved to be full of significance to both the president and Virginians. The president left the mountaintop retreat to attend the First Presbyterian Church in Staunton. The cadet corps from the local military academy lined both sides of the main street and presented arms as he rode between their lines. Col. Starling later quoted the president as saying he had never witnessed a more beautiful sight. Starling was impressed with the town’s fine appearance. The church was where President Wilson’s father had been pastor. The preacher was Rev. Thornton Whaling, professor at the Louisville Theological Seminary, a classmate and friend of Wilson. His subject was humility and the humbleness of man. Afterwards the presidential party drove past Wilson’s birthplace, and returned to Swannanoa to prepare for departure.32

Before leaving Swannanoa the president told directors of the club that he had enjoyed his stay and hoped one day to return as a private citizen and try hunting quail again. At 3:15, the presidential flag was lowered and he and Mrs. Coolidge went to Waynesboro. At the station, they once again found the Fishburne cadets standing at attention and a crowd of 5,000 waiting to bid them farewell. As they walked to their car, the cadets saluted. The train departed just after 4:00 p.m. and arrived at Washington’s Union Station four hours later. It was said that the president appeared well rested.33

Several days later Coolidge broached an interesting idea in an article written for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch’s fiftieth anniversary edition. He wrote of the demands a president faces and suggested a “rural White House” to relieve some of the stress. He thought a suitable retreat would be a modest house near Washington, perhaps somewhere in the mountains, to escape the capital’s summer discomfort. Congress supported the idea, which revived an old proposal. Sen. Key Pittman of Nevada agreed with the idea and said all government activities should be moved during the summer. He thought Congress and the Executive could continue to perform their functions from the rural location. 34

|

| Richmond Times Dispatch November 29, 1928 |

The idea began to merge with a project for a national park in Virginia. Under the Temple-Swanson Act, the state had begun purchasing land in the Blue Ridge Mountains to turn the land over to the federal government for a park. William E. Carson, chairman of the state conservation and development commission, suggested that the rural White House could include the park, established with funds Congress had set aside for the park. It is worth noting that plans for the park eventually pointed towards several New Deal projects. As early as 1928, Carson had said, “When the Federal government establishes that national park; it will build highways through the park area, including a skyline motor trail sixty miles long along the crest of the Blue Ridge Mountains from Front Royal to Waynesboro.”35

One of the first sites suggested for the rural White House was the Swannanoa Country Club, although other sites gained favor. Swannanoa offered golf, fishing, hunting, and hiking, but it was relatively far from Washington and would have been costly to maintain. Coolidge was interested in a federal property at Bluemont, Virginia, fifty-five miles southeast of Washington. The site had contained a U.S. weather observatory but been abandoned for fifteen years. Two buildings sat on eighty-seven acres and had cost the government $500,000. December 17, 1928 three bills were introduced in Congress concerning a rural White House. The first was by Sen. Simeon Fess of Ohio and authorized a commission to study the plan and report to Congress. Sen. Guy Goff of West Virginia introduced a second bill, which suggested the retreat be located on public land in West Virginia for an estimated cost of a half million dollars. Rep. Edward Beers of Pennsylvania introduced a bill proposing the retreat be built at Buena Vista, Pennsylvania.36 Months later, on February 13, 1929, Coolidge chose the Bluemont location. Congress acted in favor of the president’s idea and passed an appropriation. Coolidge wanted to be sure President-elect Hoover approved, and Hoover subsequently visited Bluemont. The Budget Bureau estimated a cost of $48,000 to remodel and furnish a building.37 Just after becoming president, Hoover expressed dissatisfaction with Bluemont. He wanted a retreat near a river where he could fish for trout, his favorite sport. Hoover chose not to use Bluemont and Congress authorized him to select another location, on the Rapidan—but, perhaps because of Swannanoa, in Virginia.38

Notes

1 Roland L. Owens to Coolidge, March 24, 1928, Coolidge Papers, Library of Congress (microfilm).

2 C. B. Slemp to Calvin Coolidge, March 29, April 4, 1928, Coolidge Papers.

3 Washington Post, April 1, 1928; E. M. Crutchfield to Calvin Coolidge, April 3, 1928, Coolidge Papers.

4 Washington Post, May 3, 1928; Staunton News Leader, May 4, 1928; New York Times, May 12, 1928.

5 New York Times, June 1, 1928.

6 Sam H. Heeler to Coolidge, June 8, 1928, Coolidge Papers; New York Times, July 27, 1928.

7 New York Times, October 18, 1928, November 15, 1928; Washington Post, October 18, 1928.

8 Coolidge to Edwin Alderman, April 21, 1927, Papers of Edwin Alderman Alderman (microfilm), Alderman Library, University of Virginia.

9 Charlottesville Daily Progress, November 13, 1928; Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 20, 1928.

10 Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 24, 1928; Charlottesville Daily Progress, November 17, 1928; Staunton News Leader, November 27, 1928.

11 Charlottesville Daily Progress, November 26, 1928; Staunton News Leader, November 27, 1928; Charlottesville Daily Press, November 27, 1928

12 Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 28, 29, 1928

13 Charlottesville Daily Progress, November 28, 1928.

14 Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 29, 1928; Washington Post, November 25, 1928; New York Times, November 29, 1928.

15 The Waynesboro News, November 29, 1928.

16 Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 29, 1928.

17 Staunton News Leader, November 29, 1928.

18 Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 30, 1928.

19 Charlottesville Daily Progress, November 30, 1928; New York Times, November 30, 1928; Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 30, 1928.

20 New York Times, November 30, 1928; Washington Post, November 30, 1928.

21 Diary of Lewis Catlett Williams, November 29, 1928, Alderman Library.

22 Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 29, 1928; Bryan Grinnan, Jr., to Mother, November 26, 1928,

23 New York Times, November 30, 1928; Charlottesville Daily Progress, December 1, 1928.

24 Staunton News Leader, November 29, 1928; New York Times, November 30, 1928.

25 Charlottesville Daily Progress, November 30, 1928.

26 Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 1, 1928; New York Times, December 1, 1928; Staunton News Leader, December 1, 1928.

27 Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 2, 1928.

28 New York Times, December 2, 1928.

29 Washington Post, December 2, 1928.

30 New York Times, December 3, 1928.

31 New York Herald Tribune, December 1, 1928.

32 Staunton News Leader, December 2, 4, 1928.

33 New York Time, December 3, 1928; Washington Post, December 3, 1928; Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 3, 1928.

34 Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 9, 1928; New York Times, December 11, 1928.

35 Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 11, 1928.

36 Time, February 25, 1929; New York Times, December 12, 18, 1928.

37 New York Times, February 14, 1929.

38 Ibid., March 17, 1929. Roosevelt also did not like Bluemont, and in 1942 the government developed a location in Maryland’s Catochin Mountains as a secure presidential retreat. First known as Shangri-la, then a decade later as Camp David, the site provided the “rural White House” near Washington that Coolidge had recommended. See, W. Dale Nelson, The President Is at Camp David (Syracuse, 1995), 4-6.