By Jerry L. Wallace

Jerry L. Wallace is a Coolidge scholar, whose interest in Calvin Coolidge and the 1920s dates back over sixty-five years. He has been a member of the Coolidge Presidential Foundation since 1972. He has served the Foundation as a Trustee and is now a member of its National Advisory Board.

But on Friday, March 4, 1921, his life in our nation’s capital was just beginning. Coolidge had spent the 121 days since his election finishing out his second term as Governor of Massachusetts, which had ended on January 6th, and resting, speaking here and there, and preparing for his new position in an unfamiliar world that was often unaccepting of outsiders.[3] This had included a pleasant visit in mid-December by himself and Mrs. Coolidge to Marion, Ohio, to get acquainted with the President-elect and his wife, Florence.

While there, Harding, who wanted to make good use of Coolidge’s administrative, legislative, and political skills, invited him to attend Cabinet meetings on a regular basis. Coolidge accepted. This would give Vice President Coolidge a more significant and direct part in the Harding-Coolidge Administration. He would be more than just the presiding officer of the U.S. Senate as had been previous Vice Presidents.

As for Warren Harding the man, Coolidge genuinely liked him and admired his skills as a politician and public speaker. “His charm and effectiveness never failed,” Coolidge wrote in his Autobiography.[4] Concerning his sense of public service, he described Harding as being “sincerely devoted to the public welfare and desirous of improving the conditions of the people.”[5] He had first met Harding in the fall of 1915 when then Senator Harding came to Massachusetts to campaign on behalf of the McCall-Coolidge ticket. Calvin Coolidge never discredited or demeaned his predecessor to whom he owed much.

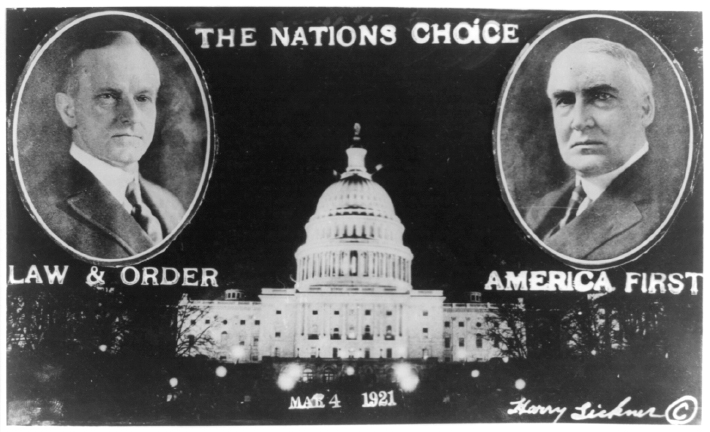

Naturally, the main feature on March 4th was the inauguration of the widely popular Warren Gamaliel Harding as our post Great War President. Unfortunately, his inauguration, which should have been a routine affair, based on custom and tradition, turned into a matter of controversy.

A few days after his election, the President-elect made it clear to those around him, including reporters, that he desired a simple, low-cost inauguration. As he himself well put it:

“If I could have my own way about it, I would walk to the Capitol on March 4, take the oath of office, speak my little piece, and then ride back to the White House on a street car.”[6]

The President-elect’s request fell on deaf ears. For the inaugural planners in Washington—one group charged with staging the official oath-taking ceremony at the Capitol and another with planning the unofficial celebratory events put on within the city—had their own very definite idea of what they desired to do.[7] And that was to put on the biggest and best inauguration in history–and they made no secret of it. To their mind, who could object to that?

Harding, who was mostly located in Marion or on vacation during this controversy, was troubled about this—and it was not simply a matter of his personal preference. Indeed, if that had been the case, one might speculate that he would have put aside his objections and let the Washington planners proceed with their elaborate plans.

At the heart of the matter, the problem was that he and Coolidge had run on a Republican platform calling for economy and restraint in government and in our national life, believing this an essential requirement for returning the country to a peacetime basis. Indeed, Harding had only recently on November 18th addressed this matter in a widely quoted speech—his first as President-elect—to the New Orleans Chamber of Commerce. There, he had pointedly said:

“Surely we are going to be called upon nationally, collectively and individually to renounce extravagances and learn the old and the new lessons of thrift and of providence. It will add to our power and emphasize our stability if we become a simple living nation once more. It will add to the sum total of our happiness.”[8]

In early January of 1921, on the Senate floor, Senator William E. Borah (R-ID), who saw himself as a watchdog over government spending, raised objections to the high cost of the swearing-in ceremony at the Capitol, stating that Harding himself was opposed to an “ostentatious display” and would avoid it if he could have his way.[9] Borah’s criticism, along with that of other Senators, received nationwide publicity. This disquiet in the Senate would soon spread to the House of Representatives as well.

Concurrently, Harding was receiving reports from Marion friends of the exorbitant prices being asked by Washington’s merchants, especially for hotel rooms. He was “horrified” and viewed this as “extortion.”[10] To this was coupled his realization of the negative political implications of an extravagant inaugural program at a time of economic slump with its high unemployment. Simply put, it would be a welcomed gift to the Democrat opposition.

Harding felt compelled to act, and so he did on the night of January 10th. Via telegram, he politely but firmly asked that all planning and arranging for his inauguration, the official and the unofficial, be abandon immediately. He wanted nothing more, he made clear, than a bare-bones inauguration–and that is exactly what the President-elect got.[11]

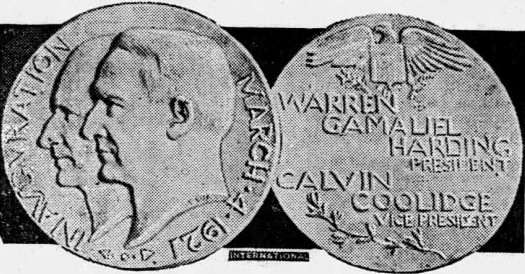

There would be no inaugural balls, no inaugural parade, no inaugural receptions, no inaugural fireworks, no inaugural medal, no first-time inaugural radio broadcast, etc. Members of Congress, newspaper editors, and the public at large responded favorably to Harding’s action.

But, of course, the inaugural planners, along with many of their fellow Washingtonians, especially merchants and society women, were disappointed and disgruntled at this unhappy end of their grand plans for the biggest and best inauguration in history, along with all the visitors and business it would have brought to the city. There was even a minority who believed Harding had no right to dictate the form or scope of the inauguration; that this was a matter for the members of Congress and citizens of Washington to decide for themselves.[12]

Calvin Coolidge supported Harding fully, issuing this statement on January 12th.

“I am in entire harmony with the expressed wishes of Senator Harding to have the inaugural ceremonies simple and free from extravagance…I feel sure that Senator Harding’s judgment is correct and will meet with general approbation. I can see no other position that he could take when the government is attempting to reduce extravagance.”[13]

As usual, Coolidge summed up the situation succinctly and fully.

As for his own Vice Presidential inauguration, it would follow past customs and traditions. There were no alterations, except one: President-elect Harding, overturning past precedent, would for the first time attend the Vice Presidential swearing-in ceremony in the Senate Chamber.

What follows is a description of principal events and happenings as they unfolded.[14]

The Vice President-elect and Mrs. Coolidge arrived in Washington, a city of 437,000, accompanied by their friends, Mr. and Mrs. Frank W. Stearns, late in the evening of February 28th. Earlier in the day, the Coolidges had been sent off with cheers and good wishes to their new home by their Northampton, Massachusetts, friends and neighbors.

The couple was greeted upon arrival in the capital by Vice President and Mrs. Thomas R. Marshall (D-IN) and Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (R-MA), along with members of the public. The Coolidges stayed at the New Willard Hotel, where they planned to make their home, since they were unable to afford the expensive rent for a suitable residence in the city on his $12,000 salary. The Coolidges were made welcomed by the Marshalls, who gave them, Coolidge later wrote, “every attention and courtesy.”[15]

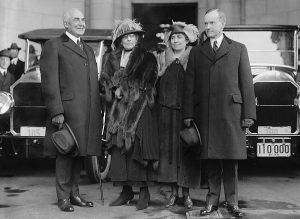

On the afternoon of March 3rd, the Vice President-elect and Mrs. Coolidge greeted the President-elect and Mrs. Harding when they arrived at Washington’s Union Station in their special car, “Superb.” After a warm public welcome, the Hardings, joined by the Coolidges, went to the Willard, where they, too, would be staying.

On the afternoon of March 3rd, the Vice President-elect and Mrs. Coolidge greeted the President-elect and Mrs. Harding when they arrived at Washington’s Union Station in their special car, “Superb.” After a warm public welcome, the Hardings, joined by the Coolidges, went to the Willard, where they, too, would be staying.

While there had been a light rain the night before, March 4th dawn sunny and bright with a chill in the air and light breeze. The weatherman advised folks attending inaugural events to dress warmly.

At about 10:00 o’clock, six cars drew up in front of the New Willard Hotel. Four cars reserved for official dignitaries, the other two, for members of the Secret Services and reporters. This little procession of motor vehicles formed the entire parade of the Harding inauguration, along with four troops of the Third U.S. Cavalry from Fort Meyers, under the command of Col. George S. Patton. With sabers drawn, the troops would ride in columns alongside the automobiles.

The members of the inaugural party—the Hardings, the Coolidges, the Marshalls, and members of the Joint Congressional Inaugural Committee—were picked up. The motorcade then proceeded at 10:20 for a short trip to the White House, where, in the Blue Room, they were greeted by President and Mrs. Woodrow Wilsons. This affair lasted about 30 minutes. Then, putting aside the old-fashion carriage, the party motored up to the Capitol building with their crack cavalry escort. Before leaving the White House, Wilson’s doctor had given him a strong drink of whiskey to brace him for the demands of the day.

Stationed along Pennsylvania Avenue were infantrymen with fixed bayonets. Harding and Wilson, accompanied by Senator Philander C. Knox (R-PA), chairman of Joint Congressional Inaugural Committee, and former House Speaker Joseph “Uncle Joe” Cannon (R-IL), were in the first car, a Packard Twin Six. Coolidge followed with retiring Vice President Marshall and other members of the Joint Congressional Inaugural Committee. Along the way, the crowds, noticeably thin compared to past inaugurals, lustily cheered both the rising sun and the setting.

Arriving at the Capitol at 11:15, President Wilson, a man broken in health, went to the President’s Room to sign nearly 30 bills—his last act as President—passed in the closing hours of the Sixty-sixth Congress. The original plan had called for Wilson to attend the swearing-in of Calvin Coolidge in the Senate Chamber and then depart, but Wilson concluded that all this would be too much of a strain for him. He called for the Vice President-elect and expressed his regrets to him in person at not being able to attend.

So it was that Woodrow Wilson, having made his bold mark on history as a great world leader, left the Capitol at 11:55 for his new home at 2340 “S” Street, N.W. His parting words to Warren Harding, “All the luck in the world.”[16] Upon arrival at “S” Street, to his surprise, the former President was greeted by a large crowd of his loyal supporters. They burst into applause and cheers for him. He was not forgotten.

In the Senate that day, the first order of business was the induction into office of its new presiding officer, Calvin Coolidge, bearing the title, “President of the Senate.”[17] These proceedings commenced at 11:45, when Vice President Marshall rapped the United States Senate to order. But there was a delay as Senators Henry Cabot Lodge and Oscar W. Underwood (D-AL) went to the President’s Room to ascertain if President Wilson had any further messages to communicate to the Senate before its final adjournment. He had none.

The swearing-in ceremony was taking place in the impressive Senate Chamber before a distinguished crowd, including President-elect Harding, members of the House and Senate, Supreme Court Justices, and envoys from foreign lands, along with other high-ranking government officials and military officers. Unlike the presidential ceremony, which had been reduced to essentials at Harding’s request, the scene in the Senate was in keeping with past ceremonies in its dignity and impressiveness. Unfortunately, we have no photographs of the occasion, since the Senators back then barred photographers from their midst.

Witnessing the ceremony from the “Vice President’s pew” were Mrs. Coolidge, wearing a red hat, with her two sons and Col. John C. Coolidge, Calvin’s father. Mrs. Harding, accompanied by Dr. George T. Harding, Warren’s father, along with 15 other family members, was also present. She wore a blue hat and a chinchilla fur.

The seating capacity of the Senate gallery was limited to around 800. These seats were filled largely, it seemed, with the wives and daughters of members of Congress. This was because Senators had two tickets to disperse and Representatives, one, and these tickets often went to female family members.

The Sergeant-at-Arms of the Senate, David S. Barry, appeared in the central doorway of the Chamber. Vice President Marshall bang his gavel. Barry announced to the assembly: “The members of the Committee on Arrangements and the Vice President-elect of the United States.” Coolidge, who had been waiting in the Vice President’s Room, then entered the Chamber, being escorted by Senator Knox and his colleagues on the Joint Inaugural Committee. The audience stood and applauded as Coolidge ascended the rostrum.

Vice President Marshall shook his hand. Those looking down from the galleries noted that Coolidge’s hair was a somewhat brilliant red. Coolidge’s entry was followed by that of President-elect Harding. It was at this point that the audience realized that President Wilson would not be attending, which was a disappointment to many. Senator Knox and former Speaker Cannon sat on either side of the President-elect.

At 12:21 o’clock, Calvin Coolidge, a son of Vermont, after a long and successful political career in the Bay State, raised his right hand with his left on the Bible and was sworn-in as Vice President of the United States by Vice President Thomas R. Marshall. Now, only one more rung remain on Coolidge’s political ladder of advancement.

Unlike for the President, no oath for the Vice President is provided in our Constitution. The oath used by Coolidge dated from 1884 and is still in use today.

“I, Calvin Coolidge, do solemnly swear that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter: So help me God.”[18]

Marshall, a well-liked figure in the Congress, noted for his humor, then delivered his valedictory address. In it, he expressed his deep faith in the American form of government and offered a warning against hasty reforms, sentiments with which Coolidge, no doubt, fully concurred. He then proclaimed the Sixty-sixth Congress adjourned sine die and handed the gavel of authority to his successor. As he did so, the audience rose and there was great applause to mark this peaceful transfer of power.

Vice President Coolidge’s first act was to call to order a Special Session of the Sixty-seventh Congress (March 4 – 15, 1921). Next, he called upon the chaplain, J. J. Muir, for prayer. Then followed Coolidge’s inaugural address.

In his brief remarks, the new Vice President was direct and businesslike. He had, it was reported, a Yankee twang and modest presence and was clearly heard throughout the chamber.[19] Coolidge spoke admiringly of the U.S. Senate, declaring it to be a citadel of liberty and noting that its records for wisdom had never been surpassed by any legislative body. The speech, while not memorable, was appropriate for the occasion and was well received. When he finished, President-elect Harding rose, turned out to face the rostrum, and joined in the handclapping. Throughout these proceedings, he had sat informally in a big armchair with his knees crossed.

Vice President Coolidge then administered the oath of office to the newly elected Senators. After which, he and his new Congressional colleagues proceeded to the inaugural stand on the east portico.

The President-elect had planned on simply taking the oath on the bear front steps of the U.S. Capitol. But fortunately, a 30-foot square platform of Corinthian architecture was provided gratis by the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T).

AT&T did so, because it wanted to test and demonstrate its new public address system to the nation.[20] What better place to do this than at a presidential oath-taking? The three large wooden amplifier horns were placed in the super-structure of the stand. And they performed their job exceptionally well. The equipment for system was housed in a special compartment below the inaugural stand, which was opened to the public after the event. This steel structure could be taken down and reused, as it was until 1981 when the inaugural ceremony was switched to the westside of the Capitol.

Thanks to the amplifier system, for the first time, the large crowd gathered in Capitol plaza could clearly and distinctly hear the new President’s words. In prior years, it was said that only those standing within 15 feet of the President could hear his address as he read it. Consequently, the crowd had to be entertained by the visual aspects of the event and perhaps band music, and of course, they could go away saying that they had witnessed a great historical event. After the ceremonies, local newspapers rush to distribute special inaugural editions containing the President’s speech.

Regrettably, plans to broadcast live the ceremony over the new medium of radio, most likely using the Naval experimental radio station NOF in Anacostia and the big Naval transmitting station NAA on Radio Hill in Arlington, had been cancelled along with other inaugural activities.[21] To have made the broadcast would have given a significant boost to radio sales and development as had the previous broadcast of the November election returns.

Chief Justice Edward Douglass White administer the oath to Warren Gamaliel Harding as the 29th President of the United States. The time was 1:18, exactly eight years to the minute from the time Woodrow Wilson took his first oath in 1913. After kissing the historic Washington Bible, Harding turned to Senator Knox and whispered, “Was it done all right?”[22]

In Harding’s day, there was no fixed time of day prescribed to mark the end of a presidential term. Thus, the need to keep track of the exact time the oath was given. This problem would cease in 1933 with the ratification of the XXth Amendment to the Constitution. It fixed the end of the presidential term at twelve noon and moved the inauguration date from March 4th to January 20th. These changes were first implemented in January of 1937.

Harding’s inaugural address, with its impressive delivery, ran 37-minutes in which he touched in a general way on the major issues and goals of his coming administration. At its conclusion, Vice President Coolidge was the first to shake the new President’s hand. Calvin Coolidge, a man of discretion and character, would always be a loyal and faithful subordinate to President Harding, always doing his best to ensure the Administration’s success in doing the people’s business.

It should be noted that the Stars-and-Stripes flying over the Capitol building had been at half-masted in honor of Representative Champ Clark (D-MO), former Speaker of the House and a much admired and respected legislator, who had died on March 2nd, but, as Harding prepared to take his oath of office, the flag was raised to full staff. Harding, who knew and liked Clark, had made a point of visiting his widow and offering his sympathy.

After his swearing-in, President Harding returned to the Senate Chamber, and there presented to the Senators the names of his nominees for his Cabinet. And, in an unprecedent move, the Senate, with Coolidge presiding, confirmed them all without further ado. It is said that the process took about 20 minutes—fast service for the U.S. Senate.

At 2:30, President Harding left the Capitol for his new home, The White House. Once there, after a 15-minute trip, luncheon was served for him and his family members. His first presidential order was to open the White House gates to the public. The gates swung open at 4:55 and the crowds rushed in and remained until late at night. The White House itself would soon be open to visitors with passes. The grounds and building had been closed to the public since early February of 1917, when the U.S. had broken off diplomatic relations with the German Empire.[23]

Calvin Coolidge later wrote this observation in his Autobiography about this Harding-Coolidge inauguration day:

“When the inauguration was over I realized that the same thing for which I had worked in Massachusetts had been accomplished in the nation. The radicalism which had tinged our whole political and economic life from soon after 1900 to the World War period was passed. There were still echoes of it, and some of its votaries remained, but its power was gone. The country had little interest in mere destructive criticism. It wanted the progress that alone comes from constructive policies.”[24]

The New Era had dawn, and with it, the XXth Century that many of us would come to know.

That night the Vice President and Mrs. Coolidge attended two unofficial inaugural balls at which they were the guests of honor in lieu of the President and First Lady, who had declined to attend.

The first was a private dinner for 200, who dined off gold and silver plate, followed by a ball with 400 additional guests, given by the McLeans, Edward and Evalyn, at their “I” Street home. It was at this “extraordinarily brilliant” affair, as press described it, that the McLeans first met the Coolidges, “who,” in Evalyn’s words, “became our good friends.” Mrs. McLean found that the new Vice President was clearly nervous—literally “shaking,” she said—and suffering a stomach-ache.[25] She was able to treat the latter with bicarbonate of soda. We are told that Mrs. Coolidge wore “a gown of tangerine colored and silver brocaded satin, made on simple lines with a panel train lined with silver.” Edward McLean, Chairman of the defunct Citizens’ Inaugural Committee, may have regretted the abandonment of a grand and festive inauguration, but by staging this spectacular dinner and ball, he made up for it to a certain extent.

The second event for the Coolidges was the Child Welfare Ball given at the New Willard Hotel. This was a charity affair and opened to the public. The ever-popular U.S. Marine Band played. Dinner was served in the Willard’s Red Room from 11 to 1 o’clock. This, too, was quite an affair attended by cream of Washington society, who had not enjoyed an inaugural ball, even if only an unofficial one, since William Howard Taft’s in 1909. Many of the guest at the McLean ball also attended the Child Welfare Ball. The Vice President and Mrs. Coolidge arrived at the Willard just before midnight, where they joined the box party of Mrs. Thomas F. Walsh, who was Evalyn McLean’s mother. Naturally, the Coolidges were the cynosure of all eyes.[26]

With this event, the Coolidges’ Inauguration Day ended. And off to bed, the weary couple went.

Afterwards:

No doubt but that March 4, 1921, was certainly a day that Calvin Coolidge would long remember. For it marked the beginning for Calvin and Grace of eight momentous years in our nation’s capital. These were years that would see him both rise to the nation’s highest office upon Warren Harding’s death, as well as suffer the tragic loss of his beloved son, Calvin, Jr.

As for the nation, President Coolidge would take up where Harding left off, carrying out and enlarging upon the constructive reconstruction policies and initiatives begun by his predecessor. Together, the Harding and Coolidge administrations helped to give rise to perhaps the most exciting, prosperous, and happy decade of XXth Century, one in which all Americans, but especially the average working man and his family, participated. With pleasure, no doubt, Coolidge addressed this happy state of affairs in his Autobiography, published in 1929, the year his Presidency concluded.

“…[By] January 1921,” he wrote, “the demobilization of the country was practically complete, people had found themselves again, and were ready to undertake the great work of reconstruction in which they have since been so successfully engaged. In that work we have seen the people of America create a new heaven and a new earth. The old things have passed away, giving place to a glory never before experienced by any people of our world.”[27]

Some historians look on Coolidge’s years as Vice President as being quite unimpressive. And this does appear to be true if you chose to focus solely on his role as presiding officer of the U.S. Senate. According to one historian, Coolidge carried out his constitutional duties in “a singularly undistinguished …and [mostly] uncontroversial manner.” Poor Coolidge, alas, was never even given the opportunity to break a tie vote. In short, he “was almost a nonentity in the world’s greatest deliberative body.”[28]

Yet, with this said, Coolidge himself held a much different view. He wrote in Autobiography, “Presiding over the Senate was fascinating to me”; and “I was entertained and instructed by the debates.”[29] Indeed, it is quite clear that he liked the job of being Vice President and all that went with it, including dining out, and he certainly held in the highest regard the Senate as a legislative body.

What some historians have overlooked is this: During this period of two years and five months, Providence gave Calvin Coolidge, a New England provincial, who had visited Washington only briefly before his inauguration and had no trusted, close friends there, an opportunity to well prepare himself for the time when he would suddenly be called to the Presidency in the dark of night. Coolidge himself later realized this and wrote of it at some length in his Autobiography.

And when that day of days did come on August 2, 1923, the new President of the United States could rightly think to himself: I can swing it.[30] And indeed, he, Calvin Coolidge, would be the right man at the right place at the right time.

Finally, what did Calvin Coolidge think about his inaugural ceremony at the Capitol? Having been sworn-in himself and participated in several inaugurations while involved in Massachusetts politics, he was not impressed at all by the Washington ceremony. In his Autobiography, he wrote:

“…I was struck by the lack of order and formality that prevailed. A part of the ceremony takes place in the Senate Chamber and a part on the east portico, which destroys all semblance of unity and continuity.”[31]

But we must note, Coolidge did not seek to correct this imperfection in his 1925 inauguration.

One wonders if Franklin D. Roosevelt read Coolidge’s comments, for in 1937, he moved the swearing-in of his Vice President, John Nance Garner, to the inaugural platform on the east portico, putting an end to the separate Senate ceremony and, also, the Vice President’s inaugural address. As a result, the Vice President’s swearing-in lost some of its distinctness, but it gained a much larger audience. Moreover, the change reflected the ever-increasing role of the Vice President as part of the Executive Branch.[32]

AUTHOR’S BIOGRAPHY

Jerry L. Wallace is a Coolidge scholar, whose interest in Calvin Coolidge and the 1920s dates back over sixty-five years. He has been a member of the Coolidge Presidential Foundation since 1972. He has served the Foundation as a Trustee and is now a member of its National Advisory Board.

Mr. Wallace is a child of the Heartland, growing up in small towns in Southwest Missouri. He is graduated of Missouri State University (BA) and the University of Missouri at Columbia (MA). He served in the US Army and US Peace Corps. By profession, he is an historian and archivist, who spent his career with the National Archives and Records Administration mostly in Washington, DC. In retirement, he established an archives for Southwestern College in Winfield, Kansas, and collaborated in writing a history of that institution.

Mr. Wallace has special experience and knowledge of presidential inauguration gained from having served as Historian-Archivists for three presidential inaugural committees (Nixon 1973 and Reagan, 1981 and 1985). He was present from when the committee opened its doors to the day, they were locked closed.

Now retired to Oxford, Kansas, he spends his time researching and writing on Coolidge and local history.

Mr. Wallace has written extensively on Coolidge, including:

—Calvin Coolidge’s Third Oath Washington – March 4, 1925 (2001)

https://coolidgefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/RCC-16.pdf

–Calvin Coolidge And The Liberty Memorial (2005)

https://coolidgefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/RCC-18.pdf

—Calvin Coolidge: Our First Radio President (2008) https://coolidgefoundation.org/blog/calvin-coolidge-our-first-radio-president/

—Recalling Calvin Coolidge: A Man of Noble Character (2010) https://coolidgefoundation.org/presidency/a-biographical-sketch-of-calvin-coolidge/

–The Ku Klux Klan in Calvin Coolidge’s America (2012) https://coolidgefoundation.org/blog/the-ku-klux-klan-in-calvin-coolidges-america/

–“Coolidge,” a biosketch on YouTube. (2012)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_yF3iISbkq8 .

ENDNOTES

[1] This is a picture of plaster cast models of the obverse and reverse of the proposed, but never realized, Harding-Coolidge 1921 inaugural medal. The picture received wide distribution in newspapers prior to Inauguration Day. The Washington Citizens’ Inaugural Committee had a medal committee charged with producing and selling an inaugural medal. Such medals had been issued since 1901, the first being the William McKinley medal. The 1921 Inaugural Committee chose Elmer Eugene Hannan (he would later change his name to Eugene Elmer Hannan), a Washington artist, to sculpt the medal. Hannan, who was well trained and had a number of artistic works to his credit, was the son of a successful Washington businessman. He had been deaf since early childhood. One can wonder if Grace Coolidge, a teacher of the deaf, might have played a role in Hannan’s selection. This is certainly an interesting possibility, but no documentation has yet been found to support it. Because of the close-down of the 1921 Committee at Harding’s request, Hannah’s medal was never struck, only this picture of the plaster casts remains. As was customary, the committee planned to present gold medals to President Harding and Vice President Coolidge, with silver medals going to certain members of the Inaugural Committee. Bronze medals were to be sold to the public, becoming a good source of revenue for the Inaugural Committee. It should be noted that after the 1921 inauguration, arrangements were made privately for another Harding-Coolidge inaugural medal. This unofficial medal was designed by Darrell Crain and struck by R. Harris & Company. Only a few medals were struck, and today, they are quite rare and expensive. See Richard B. Dusterberg, The Official Inaugural Medals of the Presidents of the United States (Cincinnati, OH: Medallion Press, 1971), pp. 47-48.

[2] By “normalcy,” Harding did not mean a return to the pre-war world of 1913, a world that, as most realized, was gone forever, but, rather, to a “peacetime basis.” The latter term was used by Coolidge during the campaign, and it appeared frequently in Republican campaign literature. It should also be noted that Harding did not coin the word “normalcy,” as it is sometimes suggested. The earliest record of the use of “normalcy” comes from an 1855 dictionary, published ten years before Harding’s birth. For details, see https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/did-warren-harding-coin-normalcy

[3] Prior to his nomination for Vice President in June of 1920, Calvin Coolidge had visited Washington, DC, on two occasions. The first was in 1916 with his wife as guests of Mr. and Mrs. Frank W. Stearns, and then again in March of 1919 when he was an attendee and speaker at the Conference of Governors and Mayors at the White House. At the Conference, Governor Coolidge gave a forward-looking speech on how to bring the country to a “peace basis.” After his nomination for Vice President, he met with Harding in Washington on June 30, 1920, to discuss campaign matters, followed by a press conference in which Harding spoke of Coolidge’s role in the upcoming campaign. On February 28, 1921, Coolidge returned to the city to established residence at the New Willard Hotel and to be inducted into office. He would remain in the city until March 4, 1929, when he returned to his rented duplex home in Northampton, Massachusetts. Thereafter, Coolidge would return to Washington only one time. In late July of 1929, at President Herbert Hoover’s invitation, the former President attended the ceremony proclaiming the Kellogg-Briand Pact.

[4] Calvin Coolidge, The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge (New York: Cosmopolitan Book Corp., 1929), p. 158.

[5] Autobiography, p. 155.

[6] “Washington In Doubt As To Inaugural Ball,” New York Herald, Nov. 6, 1920, p.1, and Harrisburg (PA) Telegraph, Nov. 8, 1920, p. 1; and “President-Elect Worried At Big Cost To People,” Lexington (KY) Leader, Jan. 12, 1921, p. 1.

[7] The two groups were: The Joint House and Senate Inaugural Committee, headed by the Senator Philander C. Knox, which was responsible for carrying out the official oath-taking ceremony at the Capitol; and the Washington Citizens’ Inaugural Committee, with Edward B. McLean, Harding’s close friend, at its head, which was to stage festive activities, such as the inaugural ball, parade, and fireworks. The former used taxpayers’ funds to carry out its task, while the latter was a private operation relying on funds obtained through donations and sales of inaugural tickets and memorabilia.

[8] “Plain Living Urged By Harding In Plea For Readjustment,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), Nov. 18, 1920, p. 1. Harding also said in this speech, “Let’s all go to work courageously and confidently, living thriftly meanwhile, and all our problems, national and domestic, will solve themselves satisfactorily enough.”…An editorial writer, noting Harding’s call for thrift and simple living, commented: “There is nothing thrifty or simple about the average presidential inauguration. If the senator [Harding] desires to set an example in simplicity and economy, Washington is afraid he may decide to begin with the inauguration.” See Anaconda (MT) Standard, Dec. 1, 1920, p. 4.

[9] “Inaugural Expense Account Is Sharply Attacked in Senate; More ‘Simplicity’ Demanded,” Salt Lake (UT) Tribune, Jan. 5, 1921, p. 8. It is worth noting that Senator Borah met with Harding in Washington on December 6, 1920. They probably spoke mostly about foreign affairs, but the matter of the inauguration most likely came up as well. Also, on February 17, 1921, Borah gave a speech on the problem of the public debt on the floor of the Senate. The task at hand, he stressed, was to reduce the debt or at least, see that the debt rose no higher.

[10] “Gouging Halted Inaugural Fete,” Spokesman-Review (Spokane, WA), Jan. 12, 1921, p. 1.

[11] Harding sent two telegrams on the night of January 10th asking that plans for the inauguration be abandoned. He may have felt a sense of urgency as, in addition to the Senate, the House was taking up the inaugural spending question. One telegram went to Edward B. McLean, Chairman of the Washington Citizens’ Inaugural Committee; the other, to Senator Philander C. Knox, Chairman of the Joint House and Senate Inaugural Committee. Both committees immediately bowed to the President-elect’s request by suspending activities. For details, including text of the telegrams, see “Plans Abandoned,” Boston Post, Jan. 11, 1921, p. 13.

[12] The popular journalist David Lawrence wrote a column supporting this point of view….It should be noted that the Presidential Inaugural Ceremonies Act (70 Stat. 1049), August 6, 1956, clearly and firmly puts the control of the Inaugural Committee into the hands of the President-elect by authorizing him/her to name it chairperson(s). The committee remains a private entity with its own sources of funding as in the past but receives under this legislation considerable support from the Federal government and the District of Columbia. The committee has also gone from being a strictly partisan activity to a nonpartisan one.

[13] “Coolidge For Plan,” Pittsburgh-Gazette, Jan. 13, 1921, p. 1.

[14] Your author relied on two articles for providing him with accurate and detailed information on the March 4th inauguration of both Mr. Harding and Mr. Coolidge. They are “Scene Centers About Retirement of Wilson; Ceremonies Are Plain,” an Associated Press (AP) account found in many newspapers; and “Harding For World Court…,” New York Times, March 5, 1921, p. 1. The AP article offer a good chronology of events of the day, while the Times article provides a good deal of interesting background information. There were, of course, many other published articles dealing with various aspects of the inaugural story that were also drawn upon.

[15] Autobiography, p. 156.

[16] Gene Smith, When The Cheering Stopped (New York: William Morrow & Co, 1964), p. 186.

[17] It is worth noting that Calvin Coolidge had also served in Massachusetts as President of the State Senate, January 1914 to January 1915, but his powers in Boston were much broader and more significant than those in Washington.

[18] See Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies website: https://www.inaugural.senate.gov/vice-presidents-swearing-in-ceremony/

[19] Joe Mitchell Chapple, Life and Times of Warren G. Harding: Our After-War President (Boston: Chapple Publishing Co., 1924), p. 164.

[20] For those interested in the details of this matter, see The Transmitter, a monthly newsletter of the Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company, for March 1921. The publication focuses on “A Telephone Achievement Ranking With the Opening of the Transcontinental Line”; that is, the use of the Bell loud speaker system installed for Harding’s inauguration. A copy of this publication is maintained at the Office of the Architect, U.S. Capitol.

[21] The Washington Citizens’ Inaugural Committee had a radio committee, made up of the top military radio experts, including Admiral W. H. G. Bullard as chairman and Major General George O. Squier from the Army Signal Corps. Their goal was to “transmit the message of the new chief executive to all parts of the United States and to the fleet.…” See “Radio To Transmit Harding’s Address,” Washington Post, Jan. 9, 1921. The day after this article appeared, Harding’s cancellation request ended their broadcast plan. By 1925, commercial radio was established, and a nationwide hook-up brought Coolidge’s presidential inauguration directly into the homes of the American people.

[22] Chapple, Warren Harding, p. 164.

[23] On Election night, November 2nd, Florence Harding declared that one of the first acts of the Harding Administration would be to “take the policeman away from the White House gates.” See Great Falls (MT) Tribune, Mar. 5, 1921, p. 1.

[24] Autobiography, p. 158.

[25] Evalyn Walsh McLean, Father Struck It Rich (Boston: Little, Brown, & Co., 1936) p. 255.

[26] For those interested in the two unofficial inaugural balls, especially participants, these articles might be of intertest: “Brilliant Affair For Charity Rivals Past Inaugural Balls,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), Mar. 5, 1921, p. 7; and “Two Brilliant Balls Add To Gayety of Inaugural,” The Washington Herald, Mar. 5, 1921, p. 1.

[27]Autobiography, pp. 137-138. Nota Bene: It is the American people, not the government, that accomplishes these great works.

[28] Donald R. McCoy, Calvin Coolidge: The Quiet President (New York: Macmillan Co., 1967), p. 134 and 135.

[29] Autobiography, p. 161.

[30] Claude M. Fuess, The Man From Vermont: Calvin Coolidge (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1940), p. 311.

[31] Autobiography, p. 157.

[32] See Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies website: https://www.inaugural.senate.gov/vice-presidents-swearing-in-ceremony/